[toc]While there were earlier studies suggesting a possible increased risk of brain tumors, lymphoma, and leukemia with aspartame, eventually the National Cancer Institute concluded those theories were incorrect and that the artificial sweetener does not increase cancer risk (32).

Whether due to that history, or other suspected side effects which are often exaggerated or even fabricated, aspartame and sucralose is frowned upon by many health conscious consumers (33).

It’s not the same as the recommend daily allowance (RDA), because that is the sufficient intake for nutrients like vitamins, minerals, protein, carbs, and other things your body needs. For food additives, when they feel it’s necessary, they do set a recommended ceiling in the form of an acceptable daily intake (ADI).

For aspartame and sucralose, the ADI is pegged at the equivalent of 75 and 23 packets, respectively.

Saccharin (e.g. Sweet and Low) falls in the middle of those two numbers… based on research, 45 packets per day is considered perfectly safe.

Is stevia better than sugar and these artificial sweeteners?

Is stevia better than sugar and these artificial sweeteners?

Most say that stevia is good for you and healthier, because it’s natural. For diabetics and those not wanting blood sugar spikes, the benefits of using it seem clear.

Is there such thing as eating too much? Certainly, its ADI must be substantially higher than those “bad” artificial sweeteners, which are allegedly unhealthy for you.

Nope.

Just 9 packets per day!

That’s the recommended maximum daily intake for stevia, if you want to stay within the ADI for a 132 lb. person (1).

The ADI is based on the high purity steviol glycosides – 95% and above – which currently is the only form of this plant allowed to be sold in the US as a food additive.

What about the natural stevia leaf, before all of the processing? Too much of that can’t possibly be bad for your health. It must be safe to eat in a large amount, without an overdose concern.

Nope.

Per the FDA…

“The use of stevia leaf and crude stevia extracts is not considered GRAS and their import into the United States is not permitted for use as sweeteners.”

GRAS stands for Generally Recognized As Safe. That’s the FDA’s designation for any substance which is intentionally added to food (a food additive). With GRAS designation, it’s considered safe by experts.

Whole dried or fresh stevia leaves are not considered GRAS. Nor are the less refined “crude” extracts. Whether it’s high fructose corn syrup or raw cane sugar you’re comparing it to, all other forms of sugar are really better for you than stevia in the crude form or the whole leaf, according to the FDA.

Before even digging deeper, this information raises eyebrows. Why is the ADI for the allegedly evil aspartame over 700% higher than healthy stevia?

In fact, out of all eight “high intensity” sweeteners which are allowed to be sold in the US and listed on the FDA’s webpage about them, this leaf-derived sweetener has the lowest ADI.

It’s not even close to the others.

Those other so-called bad for you artificial sweeteners each have an ADI which is at least twice that of stevia. In fact, one is 546x higher (advantame).

The only exception or exclusion is monk fruit. Its listed as “NS” and the footnote associated with that reads:

“NS means not specified. A numerical ADI may not be deemed necessary for several reasons, including evidence of the ingredient’s safety at levels well above the amounts needed to achieve the desired effect (e.g., as a sweetener) in food.”

So clearly, the FDA is not just ganging up on so called natural sweeteners, because monk fruit seems to get the most favorable safety review among all. None of the others get the “NS” designation.

What is stevia made out of?

The sweetener is made from the steviol glycosides found in the leaf.

There are others, but for the sake of simplicity the four major steviol glycosides and their concentration by weight in the leaf are (3):

- Stevioside (5–10%)

- Rebaudioside A (2–4%)

- Rebaudioside C (1–2%)

- Dulcoside A (0.5–1%)

A high percentage of rebaudioside A (Reb A) is what manufacturers strive for, because that’s the part with the least bitter aftertaste.

But as you see, Reb A is only 2–4% of the leaf’s content. To obtain a high concentration of it is no easy task.

How it’s made

Ordinary methods you would expect to work, like boiling or refining through a centrifuge, just don’t cut it. Breaking down these plant cells to their constituent parts – so the desired parts can be separated – requires some serious ingenuity.

Is stevia Paleo friendly? It’s such a complicated production process, you’re not even allowed to call them a natural sweetener in Canada. This is what their Food Inspection Agency says about that (4):

“Steviol glycosides are not considered to be a natural ingredient due to its significant processing and the types of solvents used for its extraction and purification. Claims which create the impression that the steviol glycoside itself is natural are not permitted. Therefore, steviol glycosides cannot be described as a natural sweetener.”

What does the word “natural” mean in the US? According to the FDA (5):

“FDA has not developed a definition for use of the term natural or its derivatives.”

That explains why there are so many “natural” foods for sale today!

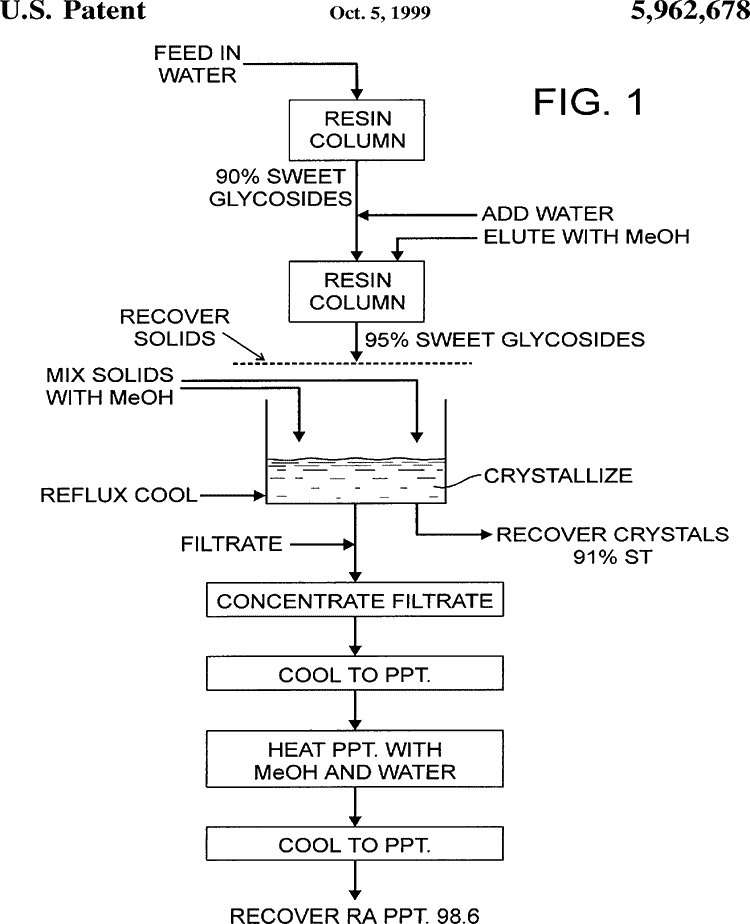

There are hundreds of patent applications which have been filed related to the stevia refining process, to make the sweetener. The following wire frame is from a 20+ year old filing which had actually lapsed (6).

That’s an example of a less complicated production method which might have been used in the early days.

There are a plethora of different methods used, some involve chemicals like chloroform, hexane, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, aluminum sulfate, or other things which don’t sound too appetizing.

Solvents aside, just trying to wrap your head around even one aspect of production, like heating and cooling, can make your head spin.

In the 00’s, another method might involve “cooling it a second to at or below a freezing temperature of about -20° C” (-4° F) (8).

Or maybe instead, the “mixture is held at a temperature of about 118-125° C. for a period of about 50-70 minutes” (9). Keep in mind that boiling is 100° C.

Whether hot or cold, what comes out of those are not exactly what you would consider a raw food or something you should eat on a Paleo diet, right?

Chemical solvents, if not animal derived, are at least considered vegan, we think. They should be gluten free too!

Today how stevia is made is an elaborate process which is difficult comprehend. In fact, on a lot of the more recent patent filings, you don’t even see them attempting to depict it all in wire diagrams.

In short, the takeaway is that yes, all stevia sweetener on the market really is made out of the actual leaves. Yes, the compounds you eat are found in the natural plant (assuming it’s a non GMO variety). Is stevia bad for you because it is processed? No.

That being said, how close the end product is to the original source is kind of like saying we as humans are all made of stardust. It goes to show you just how stupid some of the Paleo diet websites and their followers are, because many are claiming this laboratory concoction is good for you, if want food comparable to what Paleolithic humans ate. That’s funny because even refined sugar has gone through less processing than this stuff!

Side effects of stevia

According to the International Stevia Council’s website (10):

“Based on the positive safety opinions of this sweetener, stevia leaf extracts are safe and harmless – like every other approved food.”

What does “based on the positive safety opinions” even mean? Does that mean they’re just basing off of positive opinions to come up with the “safe and harmless” label?

Regular sugar is an “approved food” but would any reasonable minded person make a blanket statement and go so far as to say it’s safe and harmless? Is “every other approved food” really harmless just because it’s approved?

Another result near the top of the list was from 2010. It reported an “anti-obesity” benefit for mice which were fed a high-fat diet (12). Makes sense, given that it’s zero calorie.

Are there stevia allergy symptoms you should be on the look out for?

Published in a 2015 issue of Food and Chemical Toxicology, the authors pointed out that the plant is a member of the Asteraceae family. Ragweed, goldenrod, and other potent allergen-producing plants are also in the Asteraceae family (13).

However, these American researchers pointed out that the few published case studies of people allergic to stevia were before the highly-purified forms hit the market in 2008. Since then, they claim:

“…there have been no reports of stevia-related allergy in the literature since 2008.”

So far everything sounds great, so is stevia bad for you?

Not all, but for a fair amount of the research listed in PubMed, if you look at the end of a given paper for the conflicts or funding disclosures, you will notice many are receiving money from the sweetener manufacturers or those who have some other vested interest in promoting them. So it’s no surprise that out of the 59 results, so many are a glass half-full narrative.

To be clear, those are still true and accurate pieces of research. It’s just that many don’t seem to be really focusing on other potentially negative things.

If you dig deeper, you will find some unflattering things within those 59 results.

Published in Clinical Medicine, “an overview of systematic reviews” was done by researchers at a UK med school back in 2013 (14). Basically, they compiled reviews done by others and then drew conclusions based on those.

Using 50 different systematic reviews, 50 purported herbal medicines were evaluated, with this sweet bitter leaf being one.

Herbal medicine? The South American Guarani Indian tribe have historically used it for medicinal purposes. More recently, some Ayurvedic and eastern medicine followers make use of it.

Only 4 out of the 50 herbs had serious side effects. Among those, of most interest would probably be cinnamon and its side effect of liver toxicity.

30% of them (15 out of 50) had been categorized as having “moderately severe adverse effects” and Stevia rebaudiana was listed among those. Unfortunately, they don’t provide further details other than placing the herb in that category. And in defense of the sweet leaf, it’s worth noting that 31 out of the 50 had “minor adverse effects” noted. So all 50 were said to have at least something bad or potentially unhealthy about them.

A 2014 study out of the European county of Latvia suggested that stevia may have a negative effect on probiotic bacteria. Six different strains of Lactobacillus reuteri were tested in the lab. That’s something naturally found in human gut flora. Just about every probiotic dietary supplement on the market contains strains from the genus Lactobacillus, some containing several different versions.

Both stevioside and rebaudioside A were found to inhibit the growth of all 6 strains tested. As far as the significance of this finding, they said (15):

“Stevia glycosides application in food is increasing; yet, there are no data about the influence of stevia glycosides on Lact. reuteri growth and very few data on growth of other lactobacilli, either in probiotic foods or in the gastrointestinal tract. This research shows that it is necessary to evaluate the influence of stevia glycosides on other groups of micro-organisms in further research.”

Pay attention to the bold. Gut flora have to do with the reported mutagenic side effect seen in animals, as well as cultured bacteria obtained from human feces which suggest similar. More on that later.

In 2016, another interesting piece of research came out of India. Under financial support and sponsorship they list “nil” so presumably, they don’t have an agenda (16).

This sweet leaf was only one of 6 sugar replacements discussed. The others were aspartame, sucralose, acesulfame-K, saccharine, and neotame. About all of these, they allege:

“There is a lack of properly designed randomized controlled studies to assess their efficacy in different populations, whereas observational studies often remain confounded due to reverse causality and often yield opposite findings. Pregnant and lactating women, children, diabetics, migraine, and epilepsy patients represent the susceptible population to the adverse effects of NNS [nonnutritive sweetener] containing products and should use these products with utmost caution.”

That statement was not in reference to any single one, but apparently all 6 of those sugar substitutes.

Though aside from blanket statements like that for the category, the tidbits of info they said specific to stevia was not necessarily bad. For example, they said the stevia benefits for diabetics are inconclusive and if there is an effect on blood glucose, it may only be minimal. For high blood pressure, they said the rodent models suggest it “might be beneficial.”

If you search for this herb along with the word genotoxic, PubMed only produces 6 pieces of research.

The most recent is from 2009, which is a paper about past studies (17). They say that bone marrow micronucleus tests in mice at dosages of up to 750 mg per kg of body weight (that’s a lot) came back with no genotoxicity. Likewise for even higher dosages in rats.

What are the world’s regulatory bodies saying about this?

If you look at the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) journal from 2010, they conclude that at an ADI of 4 mg/kg of body weight per day, stevia is not carcinogenic or genotoxic based on the numerous scientific expert panels and studies conducted by national and international food safety agencies (18) (19).

Going back to the types of side effects which you don’t need a microscope to diagnose, the Mayo Clinic mentions stevia may cause “mild” ones like “nausea or a feeling of fullness” (20).

As far as entire leaf or “crude” versions of it, they say effects on kidneys, reproductive system, heart, and blood sugar are what the FDA has concerns about. However all of FDA approved food additives being sold in the US today are not those crude versions, they are the highly refined 95%+ concentrations of steviol glycosides.

In a nutshell…

Even though it really should have some caveats attached, it turns out the trumped up statement of saying stevia is “safe and harmless” is actually a fair conclusion to make, at least when it comes to the obvious and easily detectable side effects, using typically consumed amounts of the sweetener.

There’s not really sufficient evidence to suggest things like headaches, gas, bloating, diarrhea, stomach aches, etc. At least with the amounts that a human would consume.

To be clear though, that’s referencing pure stevia extracts.

However for the active ingredient – which might make up 1% or less by volume of a ready-to-use packaged sweetener – those side effects are not happening.

As far as being nauseous and feeling full, which were mentioned casually on the Mayo Clinic website, those are not things which seem to be backed by much research.

For adverse effects which require a microscope to detect, that research also paints a positive picture.

Even though the genotoxicity studies take place in Petri dishes and small animals, they are good ways of diagnosing that potential problem. With those coming back as negative, based on research to date, indeed one can reasonably conclude that stevia is not genotoxic, it does not cause cancer, and is perfectly safe to eat.

But there is one big elephant in the room. What we have discussed so far is the leaf in different forms, which includes the highly processed “natural” sweeteners you buy at the store, as well as the whole leaf (which is not for sale as a food additive). These forms are primarily what is being tested.

Not many people seem to be talking about how stevia is digested, and the forms of molecules which might result after the steviol glycosides are broken down by bacteria in the digestive tract. What happens then?

Genotoxin vs. mutagen

All mutagens are genotoxic, but not all genotoxins are mutagens.

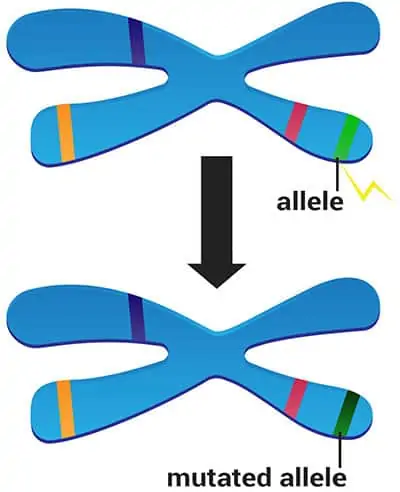

A mutagen is something which causes a genetic mutation that’s permanent.

For example, radiation is a mutagen. It causes permanent changes in the DNA sequence that are retained and passed on later in somatic cell divisions.

In other words, after the damage is done, there’s no reversing it.

Even though they stick with us, most cell mutations do not lead to cancer.

While mutations may sound scary, they are an inevitable part of life and aging. You experience them daily.

Many call them harmless but the truth is, no one really knows what kind of immeasurable side effects they may have. Scientists do not even know what causes aging, but many theorize it’s the cumulative effect of mutations throughout our life.

No one would say a mutation in and of itself is good for you, but just because something is mutagenic, that does not mean it’s necessarily bad for you overall.

For example, UV from sunlight causes mutations. But in careful and limited moderation, when you factor in the overall benefits of vitamin D production triggered by the UV, it is generally considered healthy.

A genotoxin is something which damages DNA. That might causes a mutation (making it a mutagen, too) or it might simply result in cell death (meaning its effects are non-permanent). The latter is preferred, as this “bad” cell will die off and therefore, its damage won’t be passed on.

It has been estimated that we experience DNA damage 10,000 to 1,000,000 times per day. Big numbers, but on a relative basis it’s 0.000165% of the human genome. We are quite good at repairing that damage naturally, but not all is repairable (21). When damaged DNA can’t be fixed and it slips through the cracks – remaining with us – then it is considered a mutation.

If you are still confused, it’s understandable.

This biggest takeaway is that while both are bad for you, mutagens are worse than genotoxins. This is because a genotoxin may or may not result in permanent DNA damage. However with mutagenic damage, it’s always permanent.

A mutagen can cause certain diseases, including cancer (22). When they can cause cancer, then they are also called a carcinogen.

Does stevia cause cancer?

In Japan, based on 1996 lab tests conducted using hamster lung cell lines, the following was said (23):

“These results suggest that steviol is mutagenic to S. typhimurium TM677 in the presence of S9 mix and also that rfa mutation, deficiency of excision repair and presence of plasmid pKMlOl are all required for the maximum mutagenesis.”

S. typhimurium = the bacteria Salmonella typhimurium.

TM677 = a specific strain for this type of bacteria.

S9 mix = This is a product of an organ tissue frequently used for assessing mutagenic potential.

While they did have this one positive, all their other tests came back as negative.

Considering the dosage used in that positive test, the specific circumstances required for obtaining it, and the fact that other tests throughout the two decades since then have produced negative results, it’s safe to conclude that stevia is a not a mutagen.

Therefore, stevia does not cause cancer.

But after gut flora break down steviol glycosides into other compounds, is it possible that answer might change? Then does it become a mutagen, or worse yet, a carcinogen?

What happens in rats…

Rewind back about a decade before that last study, to this one which was published in 1985. In it, you will hear about that same TM677 strain (24).

Title: Metabolically activated steviol, the aglycone of stevioside, is mutagenic.

Year published: 1985

Researchers: Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy and Program for Collaborative Research in the Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Health Sciences Center, University of Illinois at Chicago

According to them, unmetabolized steviol was not the concern:

“Consistent with reports in the literature, we have found that stevioside is not mutagenic as judged by utilization of Salmonella typhimurium strain TM677, either in the presence or in the absence of a metabolic activating system. Similar negative results were obtained with several structurally related sweet-tasting glycosides.”

In other words, their tests using the TM677 strain were also negative. But when they evaluated the effects inside actual living rats, the story changed. They said:

“However, steviol, the aglycone of stevioside, was found to be highly mutagenic when evaluated in the presence of a 9000 X g supernatant fraction derived from the livers of Aroclor 1254-pretreated rats.”

Emphais added by us. Near the end of the study, they say:

“…complete metabolic conversion of stevioside to an active mutagenic species by human enzymic systems involved in the biotransformation of endogenous substrates or xenobiotics is possible.”

It’s important to mention that Aroclor 1254, which the rats were treated with, in itself is not a naturally occurring substance. The Aroclor chemicals were produced by Monsanto and are no longer made. They had their own harmful health effects associated with them (25). So it’s not like this was a study looking at rats treated with just plain stevia.

However both this 1985 study and the 1996 study suggested that a metabolic byproduct of stevia could be produced which demonstrated mutagenicity.

It wasn’t until much later, in 2003, when a study published by Japanese researchers (26):

Title: In vitro metabolism of the glycosidic sweeteners, stevia mixture and enzymatically modified stevia in human intestinal microflora.

The first sentence of the study’s discussion section says this:

“The pharmacokinetics of stevioside are well documented from in vivo and in vitro studies in rats, but the metabolism of stevioside and its related compounds in humans is basically unknown.”

Even in 2003, the metabolism of stevia in humans was “basically unknown” at least in their opinion.

“To our knowledge, this work provides the first evidence on metabolism of stevia mixture and enzymatically modified stevia by human intestinal microflora.”

That may seem hard to believe, as you would hope these types of things were thoroughly tested in humans. But as of 2003 at least, they weren’t, at least in the opinions of these scientists.

Mentioned above in the more recent 2014 study about the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri, they claimed there was “no data about the influence of stevia glycosides” involving that probiotic. That too seems hard to believe, given it was not that long ago.

It appears there is a limited research looking at how this sweetener interacts with bacteria in the human digestive system.

While the 2003 study didn’t test actual humans, you could argue they did the next best thing:

“Degradation was examined by incubating stevia mixture, enzymatically modified stevia, stevioside, rebaudioside A, a-monoglucosylstevioside, a-monoglucosylrebaudioside A and the aglycone, steviol with pooled human faecal homogenates (obtained from five healthy volunteers) for 0, 8 and 24 h under anaerobic conditions.”

In plain English and unscientific terms, they took poop from 5 different people, mixed it with stevia, and incubated it in an airtight environment to try and to replicate what goes on in the human colon.

Their findings were…

“In summary, stevia-related compounds (including its a-derivative, enzymatically modified stevia) are degraded finally to steviol, the aglycone by human faecal homogenates. There is no apparent species differences in the intestinal metabolism of stevia-related compounds between humans and rats. Substratesubstrate interaction is observed in the in vitro metabolism of stevia mixture in human intestinal microflora, suggesting that this phenomenon may occur in vivo.”

Even with the consideration of the above, the answer as to whether stevia causes cancer after digestion remains the same – there is no evidence of that.

Whether you’re talking about the form it’s in before you eat it, or what it turns into after you eat it, you cannot call it a carcinogen.

Regardless, the evidence does still suggest metabolites of it might be mutagenic after being consumed and broken down in the body. That’s not exactly comforting news. Refined sugar may not be healthy or offer you benefits, but might it actually be better for you in light of these findings?

Let’s add this all up…

- As far back as 1985, there is a rat study suggesting the conversion to a mutagenic byproduct.

- There is a 2003 study using human fecal matter, which claims there are “no apparent species differences” with the intestinal metabolism of stevia in rats and humans.

- Even in 2014, there is a study about the reaction it appears to have with the probiotic, Lactobacillus reuteri., and the researchers say there was “no data about the influence of stevia glycosides” on this probiotic – which is found in humans – prior to their study?!

Okay, so it’s confirmed to be completely safe and non-toxic before digestion, but how much do we really know about what goes on with it afterward?

Are these findings dangerous?

In 2016, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives, 82nd edition, was published. It states (27):

“The Committee concluded that this human toxicokinetic study on a small number of males does not provide a reliable estimate of the variability in toxicokinetics, especially the conversion of steviol glycosides to steviol, in the human population. Therefore, the study cannot be used to justify the use of a chemical-specific adjustment factor to derive an ADI for steviol glycosides. The current ADI of 0–4 mg/kg bw, expressed as steviol, was confirmed.”

So this human study doesn’t provide a reliable estimate on conversion.

Indeed, this was a “small” study. Published in 2016, it consisted of just 10 males (28):

They received 40 mg of stevia per kg of their body weight, while rats in the same study received 1,000 mg per kg (25x higher amount than the humans, by bodyweight). They had found that:

“Peak concentrations of steviol were similar in rats and humans, while steviol glucuronide concentrations were significantly higher in humans.”

That’s less than 1/10th of an ounce.

The results of steviol concentrations may sound terrible, but the study’s author’s actually recommended raising the ADI for stevia. Apparently, the results weren’t considered that bad, relative to the prior assumptions used for determining the ADI.

Basically, the amount of conversion taking place in humans is currently not considered dangerous according to the World Health Organization, based on the current ADI of 0 to 4 mg per kg of body weight.

For a 150 lb. person, how much stevia per day that equals is about 272 mg.

That’s less than 1/100th of an ounce of the pure steviol glycosides, before dilution. If a sweetener has been diluted 200 fold, it would mean about 2 ounces worth.

How many sugar cookies can you bake with only 2 ounces worth of stevia powder?!

As Americans, obviously we have a sweet tooth. If we are replacing all of the sweetener in our diet with stevia, then how much are we consuming per day?

If we turn to the 2005 edition of the same report, WHO provides estimates for that scenario (29). Though keep in mind they’re assuming a 1 for 1 replacement of regular sugar you would have ate regardless. It’s not accounting for an extra intake of stevia on top of that, which you may very well be doing since it’s zero calories, right?

| Summary of exposure estimates | |

|---|---|

| Estimate | Exposure (mg/kg bw per day) |

| GEMS/Food (International) | 1.3–3.5 (for a 60 kg person) |

| Japan, per capita | 0.04 |

| Japan, replacement estimate | 3 |

| USA, replacement estimate | 5 |

| Dietary sugars replaced by steviol glycosides on a sweetness equivalent basis, at a ratio of 200:1 | |

The 5 mg/kg for the US is 25% higher than the current ADI!

Many people with diabetes, especially the type 1 diabetics, may very well be replacing all of their dietary sugars with this on a daily basis. Why isn’t anyone warning them about this?

And that was back in 2005. While that estimate is based on a “replacement of all dietary sugars” in the diet, without a specific dietary food and beverage breakdown, you have to wonder what they are including.

Twelve years later, many of us are chugging stevia-sweetened soda and water all day long because it’s zero calorie.

To count that as a “replacement of dietary sugars” may not be fair, because if stevia soda didn’t exist, many of us would NOT be drinking sugar-based soda in lieu of it. It’s not a replacement of dietary sugar, but an additional intake of a sweetened beverages for many of us.

If we didn’t have this “natural” zero calorie beverage, many of us would be drinking more water, lemon juice, and low sugar beverages instead. Not classic Coca Cola.

The takeaway

Today, it would be impossible to settle the debate of stevia vs. sugar health benefits/disadvantages. Just because the former is better for diabetes and blood sugar, it doesn’t mean the latter is automatically worse in every circumstance.

There was no increased cancer risk detected in any animal study (31). Based on research to date, stevia is not a carcinogen. There is no proof of it causing cancer.

But then again, mutating DNA is never a good thing, even if it doesn’t cause enough mutations to trigger tumors.

While the possibility remains a concern, based on research to date, stevia consumption continues to be considered safe by the World Health Organization in amounts up to the ADI.

Both the WHO and the FDA have the same ADI of 4 mg per kg of body weight as being a healthy maximum daily intake. Remember, that equates to only 9 sweetener packets in a 60 kg (132 lb) person, regardless of whether you’re male or female, a young child or an older person.

Eating too much stevia in a recipe is hard to do, if you’re using something like Stevia In The Raw individual packets. Because you can be confident that with 9 of those per day – and assuming no other dietary sources – you’re within the ADI.

Can you overdose on stevia with the liquid versions? That seems much easier to do!

Before studying this latest research, more than one of us here at Superfoodly was definitely guilty of exceeding the ADI by at least 500% per day.

That concentrated 2 ounce bottle of SweetLeaf Sweet Drops liquid stevia has 288 servings, according to its nutrition facts label. They say only use 5 drops per serving, but who uses so little? We were doing an entire dropper or two in what we thought was healthy sugar free oatmeal!

By lunch time, a couple cups of tea consumed, prepared in that same manner. Then there are the scoops of “naturally” sweetened protein powder, post bodybuilding and running. Plus, the dairy and sugar free So Delicious coconut milk ice cream for dessert! Oh yeah, and the daily 6 pack of zero calorie Zevia soda and Virgil’s cream soda, to keep that waistline in check from morning ’til night.

To stay under the ADI, you may need to incorporate another type for some of your daily sweetening needs. Try adding the the best tasting monk fruit sweeteners into your diet. Those don’t have the same safety concern associated with them.

Is stevia better than sugar and these artificial sweeteners?

Is stevia better than sugar and these artificial sweeteners?